Holocaust Memorialisation - Why it Matters

By Olivier Levy, President of the History Society

The 27th of January is the day we devote to remembering the lives lost in the Holocaust. Holocaust Memorial Day serves to ascribe humanity to the dehumanised, restore individuality to the collectivised, and give life back to the murdered. Here, The Bristorian seeks to aide that process with the first of a series of articles memorialising the Holocaust.

Why do we remember? We hold onto history because it gives us clues – a model – as to how we can better shape the present.

We take pride in some historical moments because they make us optimistic about the world, just as we reflect on shameful episodes to remind us that some historical injustices continue to prevail.

Every year, we put memories of history into practice because of the emotions they elicit. We memorialise atrocities like the Holocaust because although it is painful to imagine their horrors, their lessons remind us to interrogate the present by recalling the past.

We are also, in a sense, fortunate to be remembering the Holocaust every year. Commemorative events are widely politicised and we must recall that whilst memorialising the Holocaust is still encouraged, the same cannot always be said of: Poland, where the Law and Justice Party is shamelessly promoting exclusively heroic narratives of the Holocaust; Iran, where former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad repeatedly posited the Holocaust was a matter of opinion; and perhaps even, one day, in the UK, where Universities Minister Michelle Donelan recently proposed that prominent Holocaust deniers such as David Irving should not be blocked from disseminating their lies on campus, in the name of free speech.

The events hosted on and around Holocaust Memorial Day give us good insight into what we think of the Holocaust today, and how we keep the memory alive. As the years go by, and memories of the Holocaust begin to drift and disappear, a host of historians, artists and writers have explored different ways we think about the Holocaust and how people relate to it.

In the 1970s, New York cartoonist Artie Spiegelman began interviewing his father, Vladek, himself a survivor of Auschwitz. What resulted from 14 years of interviews, research and writing was an extraordinary depiction of the Holocaust, in the form of the 1991 graphic novel, Maus.

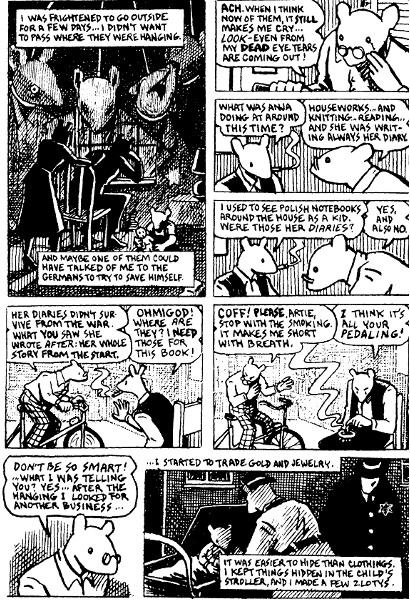

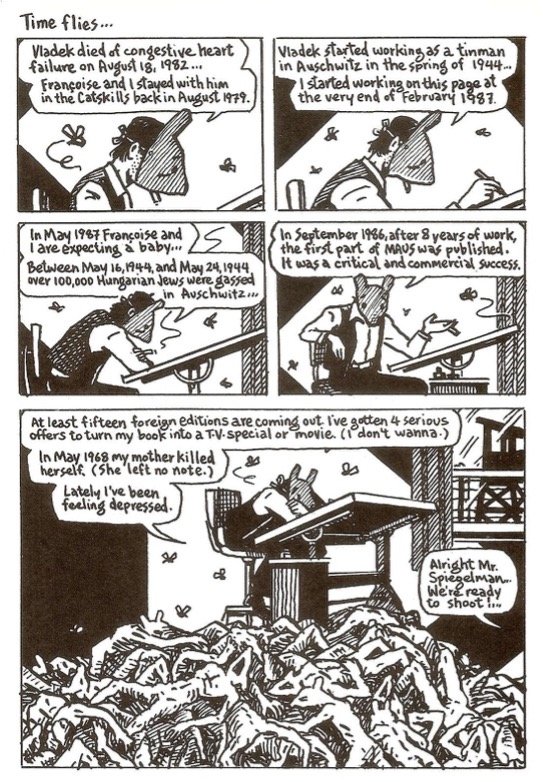

An extract from Maus, by Artie Spiegelman (1991)

Maus is useful to historians because it conveys the lingering trauma of the Holocaust. It is a piece of oral history, which in itself presents two histories: that of the past, set in Poland, and in the present, when history is being produced through interviews, research and synthesis.

The cartoon depicts not only Vladek’s life in 1930-40s Poland, as a soldier, victim and survivor, but as a witness to the genocide, being interviewed by his son, Artie, in New York City. Maus intertwines past and present into a double-stranded narrative, constantly jumping from past to present and showing how both Vladek and Artie are affected by the Holocaust forty years on.

Spiegelman caricatures the Holocaust, assigning each character to a group, and each group is represented by an animal, thereby cementing their historical role; as mice, Jews are consigned to being chased and exterminated; the Nazis are predatory cats; and Poles are drawn as pigs. Perhaps this is his way of making the Holocaust more accessible to audiences: borrowing from George Orwell, he makes his characters both less identifiable and more relatable.

Maus jumps between present and past, showing in his book the tensions that are created by Artie attempting to create an accurate version of history while remaining loyal to his father’s memories. He shows how Vladek is permanently shaped by the Holocaust, depicting the grief he surmounts, the habits he keeps, and the biases he maintains. Maus shows how we understand the pain of previous generations, how we receive it and how we react to it.

On Thursday, the Jewish Society, Generation2Generation and History Society host Vera Bernstein, who will share her mother, Alice Svarin’s, story of surviving Auschwitz. Learning about the Holocaust from second-generation survivors, rather than first, has, and will, become an increasingly common way of memorialising the genocide.

There are two main benefits listening to people such as Vera Bernstein: hearing an individual, idiosyncratic account helps us understand how the events were lived and experienced by her mother; second, through Vera’s personal story, we understand her traumatisms and gain insight into how we, and future generations, react to and experience memories of the Holocaust.

One of the characters in The History Boys (2006) claims that the best way to forget history is to commemorate it. Memorialising the Holocaust, however, reflects our rejection of racism, scapegoating and persecution, and reaffirms the values we, as a society, endeavour to hold today.