‘Fons Americanus’: Reimagining Colonial Histories in Public

By Andreia Quintal Rios, Third Year History

The cities of this country are packed with reminders and celebrations of our colonial past. So how are today’s artists and public historians attempting to decolonise their field? In this piece, The Bristorian explores the meanings behind Kara Walker’s Fons Americanus, on display at the Tate, and considers the wider decolonisation movement.

In recent years the notion of decolonising history has been a notable point of discussion within the discipline of History. Internally, changes to curriculum topics and a greater inclusion of scholarship by authors from minority ethnic backgrounds can be implemented, yet externally, the decolonisation of public history presents a serious challenge as we attempt to decolonise our collective memories.

Following the toppling of the Edward Colston statue in June last year, a nationwide discussion surrounding the future of other public monuments, which celebrate imperial histories, was initiated. In Bristol we have seen a change to names of public buildings associated with Edward Colston, such as Colston Hall, which is now named Bristol Beacon and Colston Girls’ School which has been renamed Montpellier High School. Whilst I agree with the removal of commemorations linked to colonial exploits, is the mere removal of a name doing enough?

English cityscapes are dotted with monuments associated with celebrations of empire. These monuments have acted as a means for the image of British imperial strength to be propagated for generations. Despite this connection, arguments have been made against the dismantling of statues associated with slavery, contesting against decolonisation of the past as ‘erasing history’. Kara Walker’s reimagination of the ‘Victoria Memorial’, which stands outside of Buckingham Palace, provides inspiration for the way public monuments are remembered and can be reassessed.

From late 2019 to early 2020, the ‘Fons Americanus’ was housed at the Tate Modern in London. A thirteen-metre-tall sculpture by New York artist Kara Walker, whose work has gained traction for its exploration of race, gender, and sexuality. The ‘Fons Americanus’ embodies how public monuments can be reimagined with new meanings to reshape the politics of memory.

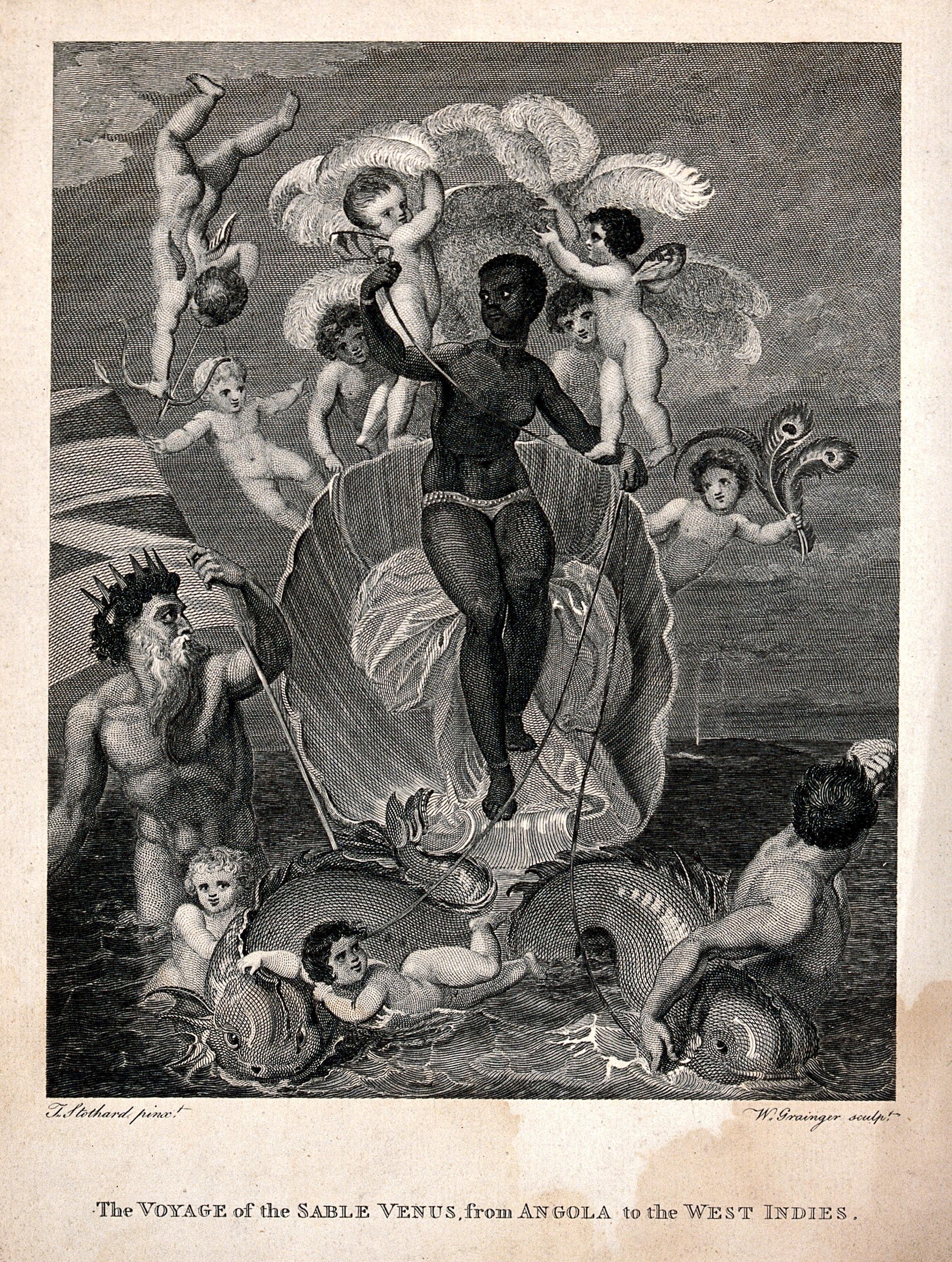

The sculpture was inspired by the Victoria Memorial, and “turns the celebrations and honouring of monuments inside out”[1] Walker reclaimed ownership of racist imagery and applied new meanings to them. At the top of ‘Fons Americanus’ is the image of ‘Venus’: this is Walker’s retrieval of the Thomas Stothard’s illustration, ‘The Voyage of the Sable Venus from Angola to the West Indies’ (1801).

The illustration propagated the slave trade, depicting Venus in a shell, being guided by Triton, a Greek god of the sea; reflections of a slave ship being guided by its powerful empire. The concept of the ‘Black Venus’ was used in eighteenth-century literary works to demonstrate the superiority of white beauty to black.[2]

Walker’s application of new meanings to allegorical figures encourages us to explore uncomfortable questions about what monuments are really honouring. This method of re-evaluating public monuments offers further opportunity to decolonise history in the public sphere.

The Victoria Memorial was erected in 1921, as a celebration of the “qualities which made our Queen so great and so beloved”.[3] As the second longest reigning monarch, and Empress of India, these celebrated legacies are bound to the violence and exploitation of colonialism. The monument also boasts two eagles, wings spread, symbolising imperial power. Public allegorical figures act as a veil by which monuments can fictionalise history into fitting with national pride, obfuscating its intwined oppression and exploitation.[4]

Meanings attached to empire are often tainted by incomprehensive knowledge of the past. A YouGov survey in 2014 saw 59% of people agreeing with the statement that “the British empire is something to be proud of”.[5] This demonstrates how associations are often made with power being respectable, without acknowledging from where this power was rooted.

Walker’s inversion of this public monument looks to reassess empire within British nationalism; breaking shallow perceptions of the past and sharing the forgotten histories which remain hidden by the veils of public monuments.

Whilst in the ‘Victoria Memorial’ depictions of ‘constancy’ and ‘courage’ are visualised surrounding Queen Victoria; in Walker’s ‘Fons Americanus’, Queen Victoria is displayed in high spirits. Yet at her foot is a ‘weeping boy’ with just his head peering out of the water; a representation of the lost stories drowned out by what we choose to remember and forget.

An importance lies in ‘reparatory history’ and reviewing perceptions of the past; engaging with the ‘forgotten voices’ and ‘untold stories’ to correct public memory.[6] The statue of Edward Colston now stands on display at the ‘M Shed’ museum. Whilst its position has been reinstated as a part of public history, its meaning has been altered.

British historian, David Olusoga, has argued that after the statue was pulled down and defaced by protesters, that it then became “a far more important and potent historical artefact”.[7] Many public statues and monuments’ meanings remain unknown to the public, their significance and power merely being assumed due to their public commemoration. In applying the context of silenced histories to our memorials, we work to reimagine and decolonise the histories that are being shared.

Black History Month adopts various forms of engagement with neglected histories, but public memorialisation is an aspect which should not be forgotten; it has constructed ideologies and perspectives of the past and promulgated the values of a period distinct from our own. We must interrogate and reimagine their meanings within the context of the present day.

So next time you pass one of the many grand monuments dotted around our cities, ask yourselves what invisible stories may lie within.

Footnotes

[1]Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/kara-walker-2674/kara-walkers-fons-americanus, (2019)

[2] Regulus Allen, ‘The Sable Venus and Desire for the Undesirable’, (2011)

[3] Thomas Brock speaking of Queen Victoria, found in: Philip Sheldrick, ‘From Flesh and Bone to Bronze and Stone: Celebrating and Commemorating the Life of Queen Victoria in the British World, 1897-1930’, (2013)

[4] Rebecca Senior, ‘Britain’s monument culture obscures a violent history of white supremacy and colonial violence’, (2020)

[5] YouGov, https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2014/07/26/britain-proud-its-empire, (2014)

[6] Catherine Hall, ‘Doing reparatory history: bringing ‘race’ and slavery home’, (2018)

[7] David Olusoga speaking on the Edward Colston statue. Damien Gayle, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/04/edward-colston-statue-potent-historical-artefact-david-olusoga (2021)